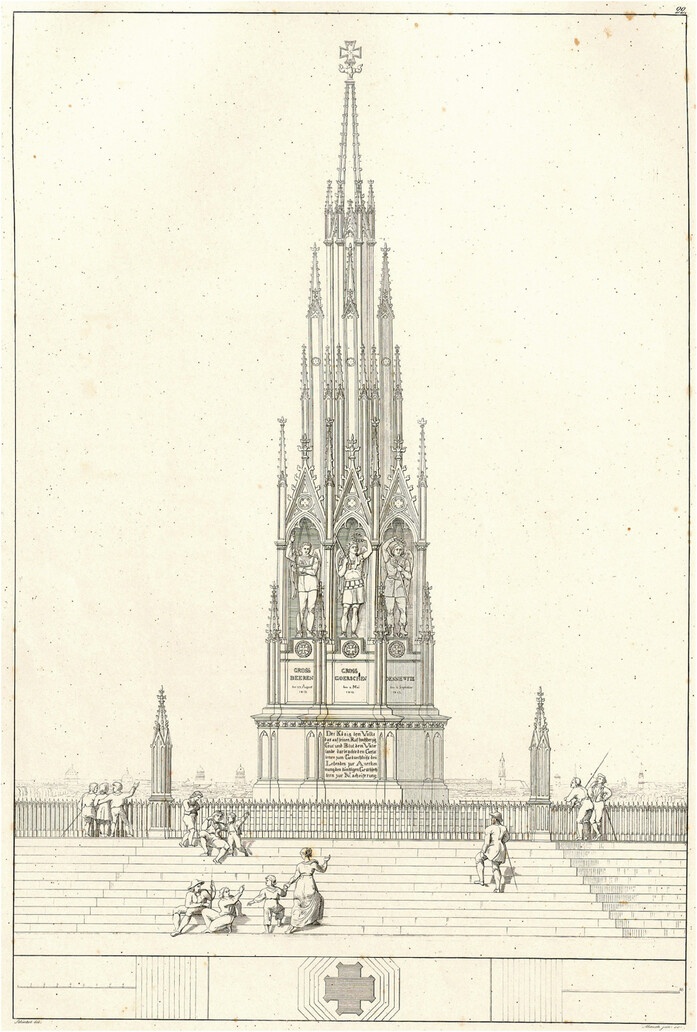

Schinkel’s cast-iron National Monument for the Liberation Wars (1821) in Berlin’s borough of Kreuzberg (itself named after the monument whose ground plan is that of a cross) commemorates the fallen Prussian soldiers who fought against Napoleon. Every side bears a plaque with a name of an important battle and a bewinged genius resembling a Prussian dignitary. Today, it is part of a park that serves as a favourite place for picnics. It is a safe bet that the monument’s historical circumstances and its symbolism are lost on most of the park-goers. But it is as equally likely that they will nevertheless acknowledge its status as a monument to something. In this essay, published in History and Theory, I investigate the question “what makes things appear monumental?” and argue in the process against the popular notion that monuments cannot but fail, eventually, in their historical mission.