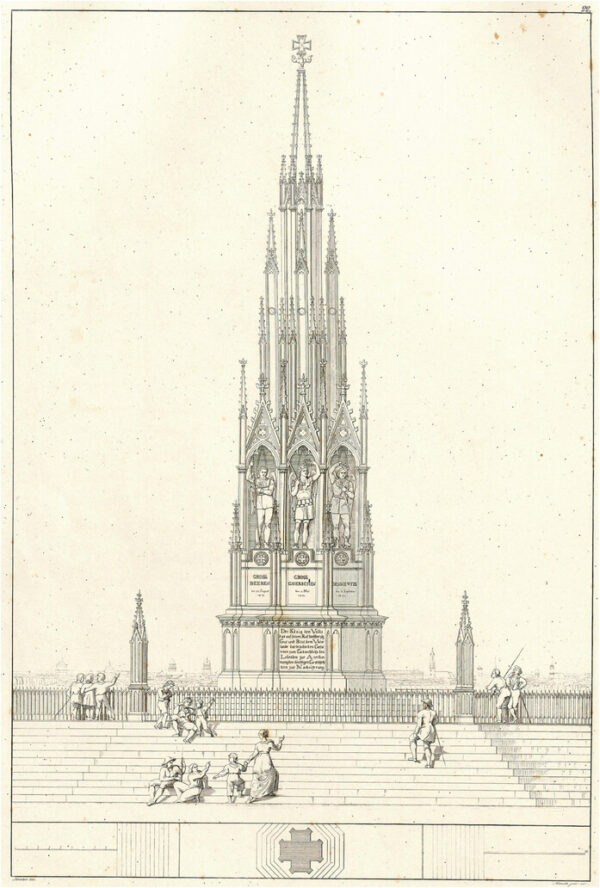

This stele, now in the British Museum, was once part of the interior of Esagila, Babylon’s main temple and the seat of Marduk, the city’s main deity. The relief depicts the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (668–631 BCE) taking part in a ceremonial moulding of a foundation brick. It deviates from standard pictorial representations of Neo-Assyrian rulers (e.g., it depicts the king en face) because it borrows from a much older visual idiom found in copper figures of Neo-Sumerian kings from the third millenium BCE. These had been buried as amuletic foundation deposits beneath temple floors and then excavated by the Neo-Assyrians involved in temple renovations.

The stele’s archaizing look is to make it appear classical, timeproof and thus to manifest the Assyrian authority’s lasting relevance. Attention to such manifestations characterizes the frame of mind of both monument builders and their future art historians. In a sense, the builders already are art historians: they deliberately produce objects of art-historical relevance. Or so I argue in my essay ‘Monumental Origins of Art History: Lessons from Mesopotamia‘.

Image source (© The Trustees of the British Museum).